My first encounter with Kelly’s designs happened to be from a featured editorial with KNUCKLE itself. Appearing in the ‘Marshland’ shoot in Issue 03 of the magazine, Kelly’s rhapsodic tableaux red dress is difficult to miss in the black-and-white shoot – the torso of the dress clings to the model’s frame, before widening out into a lampshade-style silhouette to give the impression of an exaggerated hourglass shape. A current Central St Martins’ womenswear design student, Kelly’s work has been featured in magazine editorials of the likes of Glamcult. The designer describes her own work as ‘surreal and poetic’, and this description certainly rings true – Kelly’s pieces always exude a carefully restrained, delicate air, allowing viewers a tantalising glimpse into another world. Sitting down with Kelly, we talk about nostalgia, memory, and the influence of mothers in Kelly’s womenswear design process.

First I’d like to know a little bit about your design background – how did you get into fashion design and styling, and what brought you to ultimately study fashion at CSM?

No one in my family worked in fashion or in any creative field, really, so my background in fashion is very much self-made. I first became interested in fashion after moving away from my home country, Vietnam, at a young age. I didn’t have many friends at the time, and dressing well became my way of gaining social presence and confidence. As an Asian girl living in a European country like Latvia, it was difficult to feel seen, and fashion became a form of self-expression and empowerment for me. Over time, it evolved into something deeper. I began thrifting and upcycling clothes to stand out from the crowd of Zara and H&M, and I started immersing myself in fashion shows and styling. When it came time to choose where to study, Central Saint Martins stood out to me quite naturally—not just because it’s an English-speaking institution (though that helped, of course!)—but more importantly because of the incredible creativity and individuality it fosters. It’s one of the most prestigious fashion schools in the world, and I’ve always been drawn to a challenge.

The first thing that really struck me about your work was its striking eerieness. There’s an intriguing, almost Gothic, undertone throughout your work, which is extremely interesting. Tell me a little bit about that, and your overall process for your work.

That’s actually the first time I’ve heard my work described that way, and it’s always refreshing to see how others interpret it. I suppose it doesn’t contradict with how I see my own design language. My work blends concept with wearability, always rooted in storytelling and emotion. In many ways, I feel like I’m designing for a kind of female superhero—not in the comic book sense, but as a symbol of strength, complexity, and quiet rebellion. Each collection becomes a portrait of her, a way to give her form, identity, and presence. There’s something romantic about that process, like writing love letters through fabric. I’ve also come to realize how deeply family-oriented I am. Most of my projects are inspired by someone close to me. I carry the history and spirit of the people who came before me. Their lives, their choices, the way they raised me, all of that shapes my point of view. My creative process usually begins with a heartfelt conversation, flipping through family albums, and digging through old storage spaces. From there, I begin to shape a story that speaks to a wider audience. It’s not just nostalgia; it’s about finding something universal in the personal. For example, Mom’s Night Out wasn’t just about my mom. It was a tribute to all the women in 1990s Vietnam who didn’t have the freedom to express their sexuality. That collection was about reclaiming joy, confidence, and agency—something tender and powerful at the same time.

Why are these particular themes such a draw for you and your work?

I’ll admit I have a pretty unhealthy work-life balance, and I think that’s something many creatives can relate to. Because of the intensity of it all, I often struggle to find time to be with the people I love. So instead of choosing between the two, I let my personal life become part of my creative process. The conversations I have, the emotions I carry, even small daily interactions—they all feed into the work. That’s where the ideas come from. It always begins with a conversation or something small I’ve observed around the house. It doesn’t have to be something physical—it can be a passing idea, a vague memory, or just a feeling. From there, I start building an imagined narrative around it, something new but rooted in something real. Then I begin exploring possibilities through fabric, silhouette, and styling. It’s never a straightforward process. I’m also drawn to experiences I didn’t get to live. I find myself fascinated by what I don’t know, by how things looked and felt from someone else’s point of view. That curiosity often leads me back to my family. Even though I’m physically far away, designing around their stories helps me stay connected. It’s a way of understanding them, and through that, understanding myself. It becomes a form of emotional closeness, even from a distance.

I’d especially love to hear about your Balenciaga Museo Project, Mom’s Night Out, that was featured in Glamcult. What was the design process for that like?

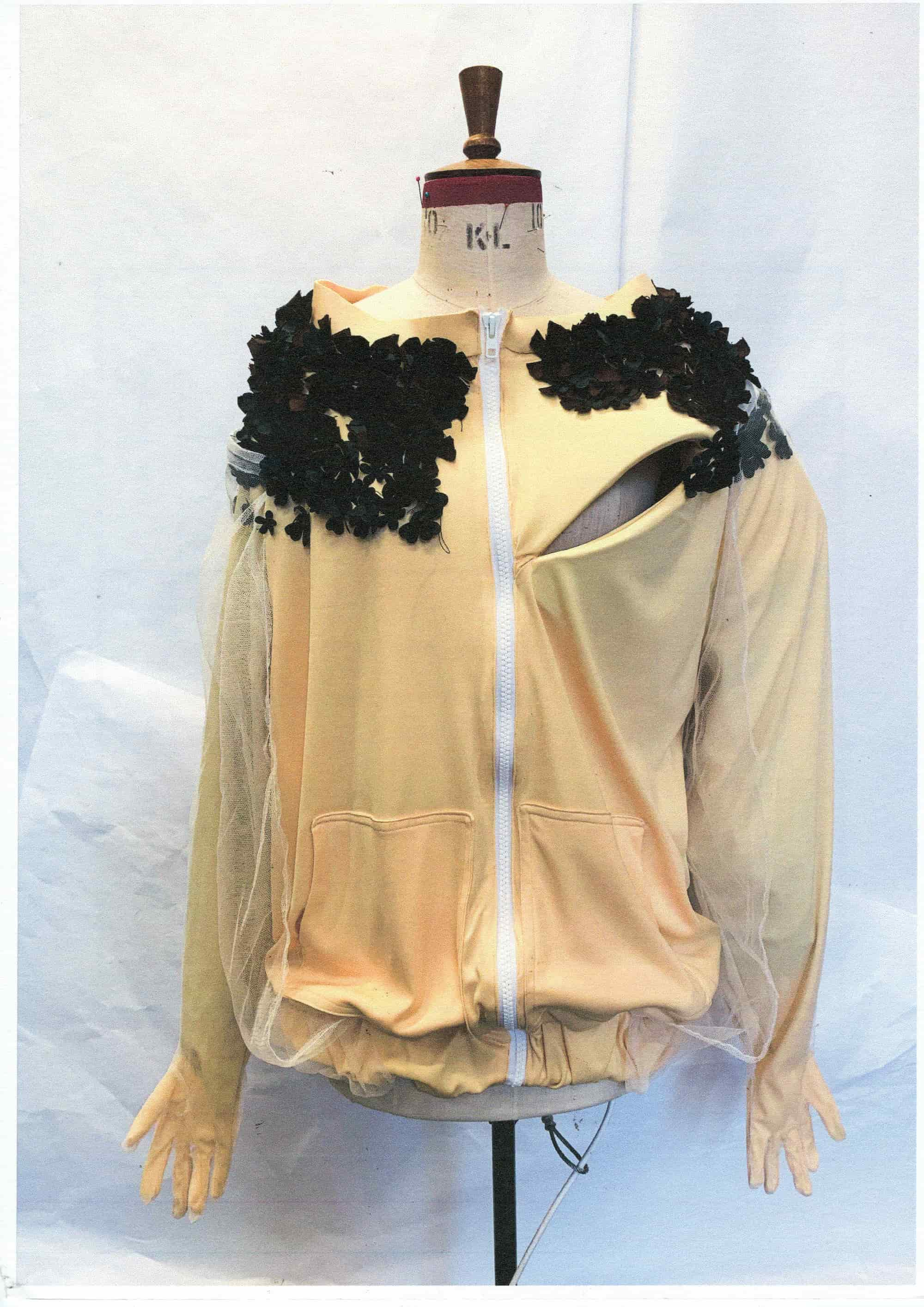

That collection started after a surprisingly honest conversation with my mom, sparked by a situationship I was going through. Out of nowhere, she told me she wished she’d had a one-night stand in her youth. I was shocked at first, but also intrigued. She wasn’t saying it out of regret or dissatisfaction with her marriage—my dad was the first person she dated—but more out of a longing for the freedom she never felt she had. It was about the shame and pressure that surrounded female sexuality when she was young, especially in 1990s Vietnam. I asked her to describe what her ideal night out would have looked like. She painted this vivid picture of post-war Saigon, with its rising western influences, cheap thrills, and rebellion hidden under uniforms. She and her friends would tutor by day and sneak out at night, wearing thinner outfits hidden beneath their work clothes. They used to make confetti from hole-punch scraps and toss it in clubs or on the street. Once, my grandfather disciplined her because he found a piece of confetti tangled in her hair. That conversation became the core of Mom’s Night Out. I designed it for the woman who’s built a stable life, has her career in check, but still wants to feel alive, still wants to experience freedom and joy. The jacket fuses formal wool with latex to reflect both responsibility and desire—it says she’s not pretending she doesn’t have a party to catch after work. The inner layer, made from organza and silk satin strips, directly references the confetti. It’s soft, sensual, and playful. And yes, it has a pocket—because you can’t lose your keys at the club.

After the success of Mom’s Night Out, what will you be going into next? Are you working on something at the moment?

I’m working on a new project, and yes—it’s inspired by my mom again. She taught me how to ride a motorbike, and that memory sparked something for me. It’s simple but full of emotion, and I’ve been building a story around it. I’m aiming to finish it by next week and I’m excited to share it. This year, I’m slowing down. After two intense years, I want to take a breath. It’s also my placement year, so I’ll be using it to intern, travel, and learn. It’s a time to reflect, to help where I can, and to challenge myself outside of the school setting. I’m also using this period as a trial—to see if I can manage bigger goals on my own terms. One of those goals is to design a collection for London Fashion Week in February 2026, if timing allows. I’ve been so inspired by this year’s CSM BA show, and I can’t stop imagining what my graduate year could look like. It’ll be a different rhythm without the usual academic structure, but I’m excited for the freedom, the experimentation, and the new stories that will come from it.