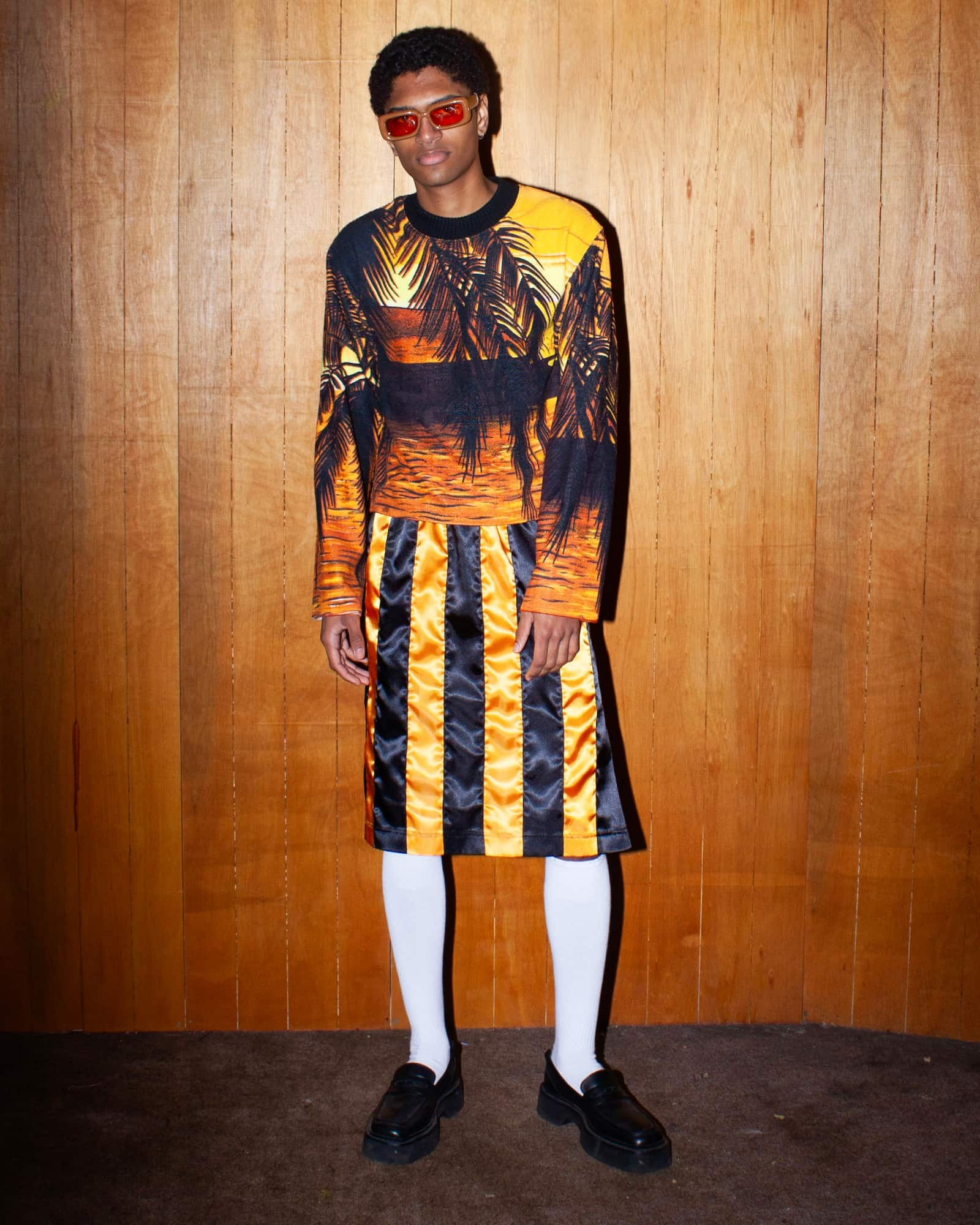

Saturated in a warm chaotic familiarity, Adam Jones’s collections are not only visually striking but deeply nostalgic. Scouring local markets, the London-based designer revitalises forgotten fabrics, reimagining football scarves and pub towels into hand-crafted garments. Drawing on his childhood memories of post-industrial Wales, Jones’s work is autobiographical, a celebration of past and present lovingly stitched together. In this conversation he reflects on his creative process, the artistic value of limitation, and what luxury means in an age of mass production.

You grew up in Wales; in what ways does that upbringing still echo through your collections today?

My upbringing in Wales is pretty much everything to me. It’s my mood board and completely inspires everything I do without me realising it. Growing up there I was always trying to get out and it felt very sheltered from the world. We didn’t have a high street, and we didn’t have the internet when I grew up, so I saw the world through TV and the Sunday Supplements. Then you get older, and you realise everything you’re making is pretty much inspired by where you came from, and the childhood you lived. I would say I feel like I grew up in the 70s not the 90s, because it was a bit of a time warp in Wales. Post-Thatcher when the mines closed, if you weren’t at home, you were being dragged to the pub with your dad. I’m also just very inspired by my home growing up, my grandma’s house, I spent a lot of time there because my parents both worked. So it’s really about the interiors of the pub and the interiors of my grandma’s house and clashing those.

Since moving to London, how has the city also had an impact on your work?

I still look for things that remind me of home. I seek out those old pubs that make me feel like I could be in Wales. I embrace where I live like a community, like a little village. In Deptford, I get to know local people and shop locally for my fabrics. As I say I grew up watching all these shows like Only Fools and Horses and living in London I feel like I’m on a TV set every day. It kind of blows my mind every day walking through Deptford market. It’s kind of the characters I see walking through my high street, butchers and fruit stall holders, that kind of old traditional London that really inspires me.

The late stylist and designer Judy Blame spotted your work on Instagram and became a mentor of sorts to you. What did his approach and creativity teach you?

He just kind of taught me to keep doing what I do. Having someone like that believe in what you do and encourage you gives you the confidence to believe in your vision. His make-do and mend approach, that kind of punk DIY, make-something-out-of-nothing, which is what I do, and what he did as well. Seeing someone that successful take an interest in my work was just everything to me.

Embarrassingly, I hadn’t heard of him before, so I did a deep dive, and he was so incredibly interesting.

Yeah, he’s an icon. I was starstruck, I couldn’t believe it. Just got to hang out with him all the time, chain-smoking at his kitchen table, making things with him. It was brilliant.

From pub towels to football scarves, working class symbols are central to your designs. What first drew you to those everyday objects and when did you realise quite what they could become?

It just comes naturally to me to use everyday materials that I see around me. Going to fabric shops has never really interested me. I just think if you buy a nice fabric and make something out of it it’s going to look good and that didn’t really excite me, so it was about trying to challenge myself to look elsewhere where others weren’t. Spending a lot of time in pubs I was naturally surrounded by beer towels and lads in football scarves, and I just thought that would be fun to try to rework those items. Growing up going to car boot sales I was naturally thrifty and had an appreciation for secondhand. It just all comes super naturally to me, not supernaturally, I mean naturally (laughing).

Your designs reference pub culture and British nostalgia, which hold positive memories for some but also negative connotations for others. How do you address that in your work?

I hopefully try to encourage people to step through the threshold of a pub that might seem intimidating, because actually they’re usually full of warm characters. I feel like it’s the only neutral space where everyone is there to have a nice time. It can kind of feel like a living room, but you meet people you wouldn’t necessarily meet or stop and talk to. It puts you on the same level, you’re all there for a drink, you all just want to have a good time. People find it intimidating maybe by the way characters look but it’s a very levelling environment, I think. Pubs have become quite trendy now and it’s encouraging kids to find the ones that are traditional and authentic, and to get to know people you wouldn’t normally come across.

I’m really interested in the phenomenon of ‘anemoia’, which is a nostalgia for a time you didn’t experience. Obviously, nostalgia is an important theme in your work, and I also notice a lot of 70s influence throughout your collections. I know you mentioned that you feel in a way you did grow up in the 70s. How do you relate to this idea of anemoia and how does it translate into the pieces you design?

I would say I totally have that. I was born in ‘91 but like I was saying Wales was quite wealthy when we had the mines and we had factories producing and exporting all over the world, and then with the closure of that it all stopped. The aesthetics of people’s homes and the high street and the pubs and what have you, it all stayed the same. So, I feel like I grew up in the 70s because of my surroundings aesthetically. And spending a lot of time with my grandparents, that enforced the feeling. Them showing me TV shows from when they were younger and you know grandparents are obsessed with getting old photographs out and showing you those. So I definitely have that.

So, you work exclusively with found materials, is that right?

Not entirely, predominantly. I make a lot of stuff out of ribbons which are 100% recycled polyester, and any canvas material is from like plastic bottles. Any virgin materials I do work with, I actively find a sustainable option.

You’ve stated that you enjoy the constraint that comes with this. Can you talk about how these physical limitations can be useful and how important the material is in dictating design decisions.

Staring at a blank piece of paper and trying to come up with an idea and sketch is something you do in University a lot and it can be quite overwhelming. I need those constraints for me to be able to work. Because where do you start? What do you do? Whereas if I have a tea towel in front of me and it’s a certain size, it can’t be a coat, it can’t be a dress, it has to be a vest or a bag. And I find that really freeing because I don’t have to think too much about what to make, the fabric will tell me. It depends on how much I have and the size of it, so it’s a huge part of the design process. The whole design process is kind of being out there and finding these materials. I never sit down and sketch and decide what to make and find the fabric for that. The fabric always comes first.

Although the materials you use are not conventionally luxurious, every piece is handcrafted and limited edition. Do you see that rarity, and the story behind the piece, as a new kind of luxury?

Yeah definitely, I think I’ve said that exact line before. Yeah, nothing is very special in the world anymore with mass manufacturing, and people have lost the appreciation for items and the things they purchase or wear. Also, British manufacturing was so strong back in the day when we made things here, so these tea towels that lasted 50 years plus, the fact they’re in such good nick and they’re so strong, hopefully turning them into a top or a skirt they’ll last another 50 years. I think it is a new kind of luxury, the rarity of it, the age of the piece, it’s old but it’s fresh hopefully.

Could you walk me through your creative process, from how you research to sourcing the material to creating the finished product.

I would say the research has been done in my upbringing, my childhood is my mood board, and I have that so clearly in my head that I don’t really need to research anymore. It’s all there, it’s just about going to boot sales, going to junk yards and looking for materials that maybe remind me of something that would have been in my grandma’s house, or a tablecloth or something that would have been in a sitcom, a wallpaper that would have been in Only Fools and Horses. The whole design process is being out there and finding fabrics that feel like they’ve come from my memory or childhood, even if they haven’t. Thinking, does that fit into my world? Usually, I spot one thing and then I scour the internet and try to find loads and loads, you know Facebook Marketplace and eBay and whatnot. As soon as I’ve got a big bulk of them then I might put it into in a collection. I don’t want the pieces to be one off, I want it to be like a real fashion brand, and you like it because of the way it looks, and it just happens to be sustainable.

That must involve a lot of digging on the internet.

Yeah, everyday (laughing) but I love that.

You must have great eBay skills; you’ll have to teach me. But where do you find them in the first place?

In Deptford we have a house clearance market three days a week, which is really helpful. Then I go to Spitalfields market on a Thursday, Covent Garden on a Monday, less and less now because I get busier, but that’s usually where I see it first and then I get straight on eBay. Then it’s about placing it on the body, twisting it on the mannequin and thinking that could be a jumper or a dress, or it’s so small it can only be a bag, and the collection naturally develops. I try to keep it a certain colour palette so it feels cohesive and like I’ve sat down and designed it all, but actually it’s quite spontaneous. So it’s about curating these items so it makes sense, because it could go a bit mental. I need a colourway or something to tie it in together even though it’s quite sporadic and natural.

Looking across your collections, over the years, how do you feel your aesthetic and process have evolved?

It’s always a development from the last one. There are staple fabrics and patterns I always use. I don’t want it to flip-flop and change. I still want people to be able to buy something I designed years ago and add a new piece to their collection. Each collection is adding pieces to this huge back catalogue of work, that hopefully all sit together still. It’s just about adding new fabrics every season. We added in lace and then I might start adding in tapestry.

I guess that mindset goes hand in hand with sustainability, because you’re continuing instead of restarting every time.

Yeah totally. Even something I made five years ago, if I see that fabric again, I’ll buy it and put it back online. Because sometimes people get added to a waitlist because they want something I made years ago and suddenly it might appear again. It has that kind of Supreme drop thing about it. Hopefully it creates demand. You have to get it now because you don’t know when it’ll appear online again.

Finally, what advice would you give to young creatives looking to carve out a space that’s authentic to them, in such a crowded and challenging industry?

It’s harder than ever right now. Well, it’s harder than ever but also easier than ever, so I guess it sort of evens out. I think you just have to be careful with algorithms, like on Instagram, because everyone is seeing the same stuW. Use your memories and what sets you apart from other people and try not to be inflflenced by things you see online. Look for alternatives, get back in the library, watch old films, think about your upbringing. I guess it’s about not being lazy with your research.